Millennial Dreams is here!

I’m very pleased to announce the publication of my book, Millennial Dreams in Oil Economies: Job Seeking and the Global Political Economy of Labour in Oman, with Cambridge University Press. After some epic production delays largely due to the cyber-attack at CUP, it finally arrived to my home on 31 December, and was available to order from the beginning of this year.

This book has been some years in the making, and is really grounded in and inspired by my long-term research experience and interactions with Omanis, and especially with Omani students, workers, and jobseekers – to whom I am immensely grateful. At the same time, the empirics and narratives of the book are grounded in a historically longer, and much larger story of global labour. It demonstrates how we can analyse economic development trajectories from the perspective of labour and from a theoretical orientation of the global political economy of labour. Methodologically inspired by the words of my interlocutors, "I begin at the margins, and centre on ‘living and working’ – I ‘follow the workers’" (p87) over time and through their experiences working and seeking work.

This has been a project very close to my researcher ‘heart.’ Fundamentally, it tries to shift the common approaches to how we discuss economic development in oil-dependent economies by bringing in labour from the margins of global political economy analysis. It thus demonstrates the analytical advances we can make by decentring oil and varying our departure points and primary analytical foci, following in the critical political economy turn in scholarship on the region (e.g. work by Hanieh with the starting point of global capitalism and Khalili on global logistics and infrastructure). This allows me to contribute to debates not only on the rentier state and on labour, but also class, unemployment, political mobilisation, radical infrastructural change, economic citizenship, and gender and work.

I trust, therefore, that this book will be of interest to those interested in Oman and the wider Gulf, as well as to scholars of comparative, international, and global political economy, and development studies more broadly.

Below, I briefly describe the contributions of the various chapters. Please do read and engage with the book. I’m looking forward to your reactions.

Chapter 1: Bringing Citizen Labour into IPE Scholarship on the Gulf

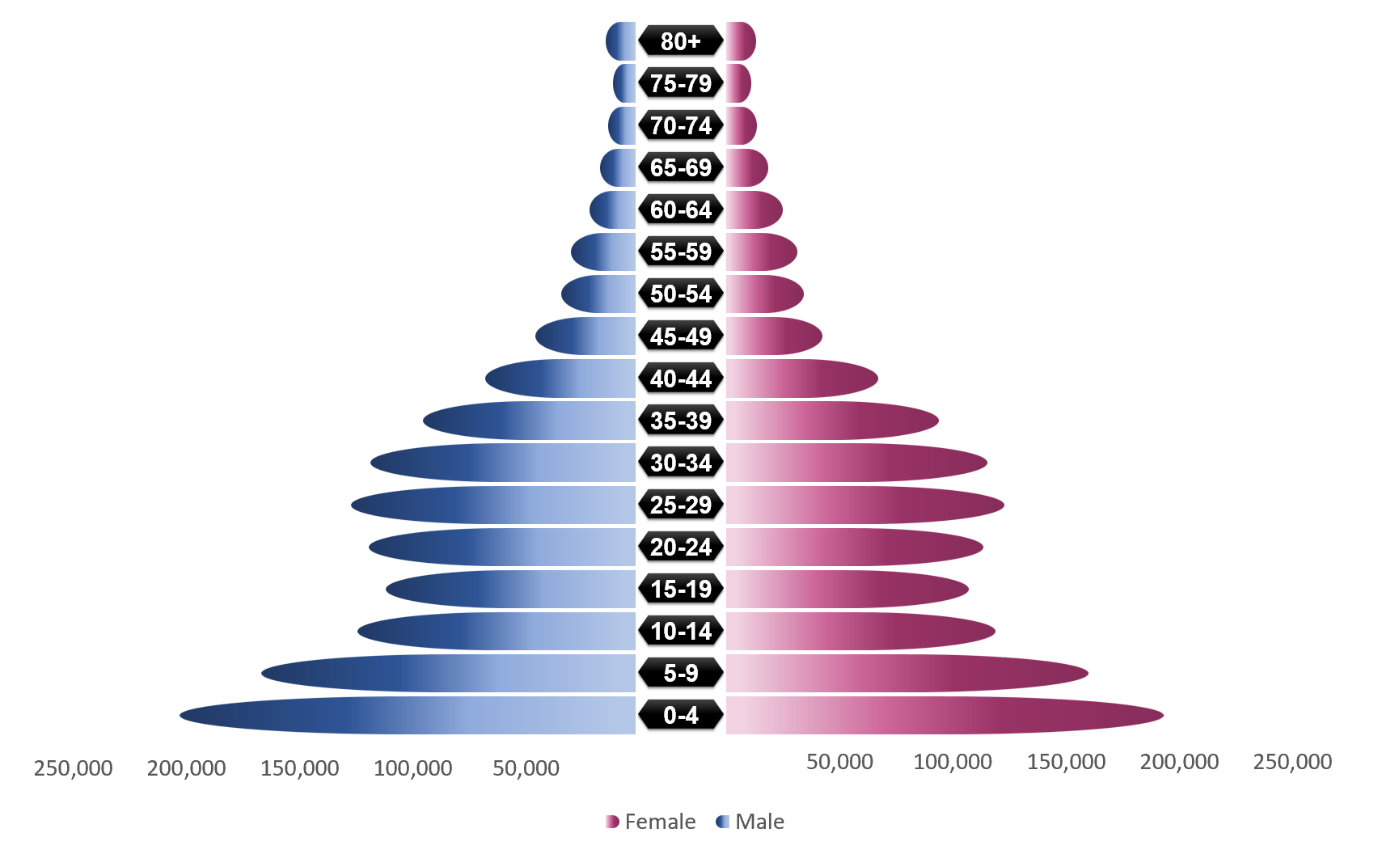

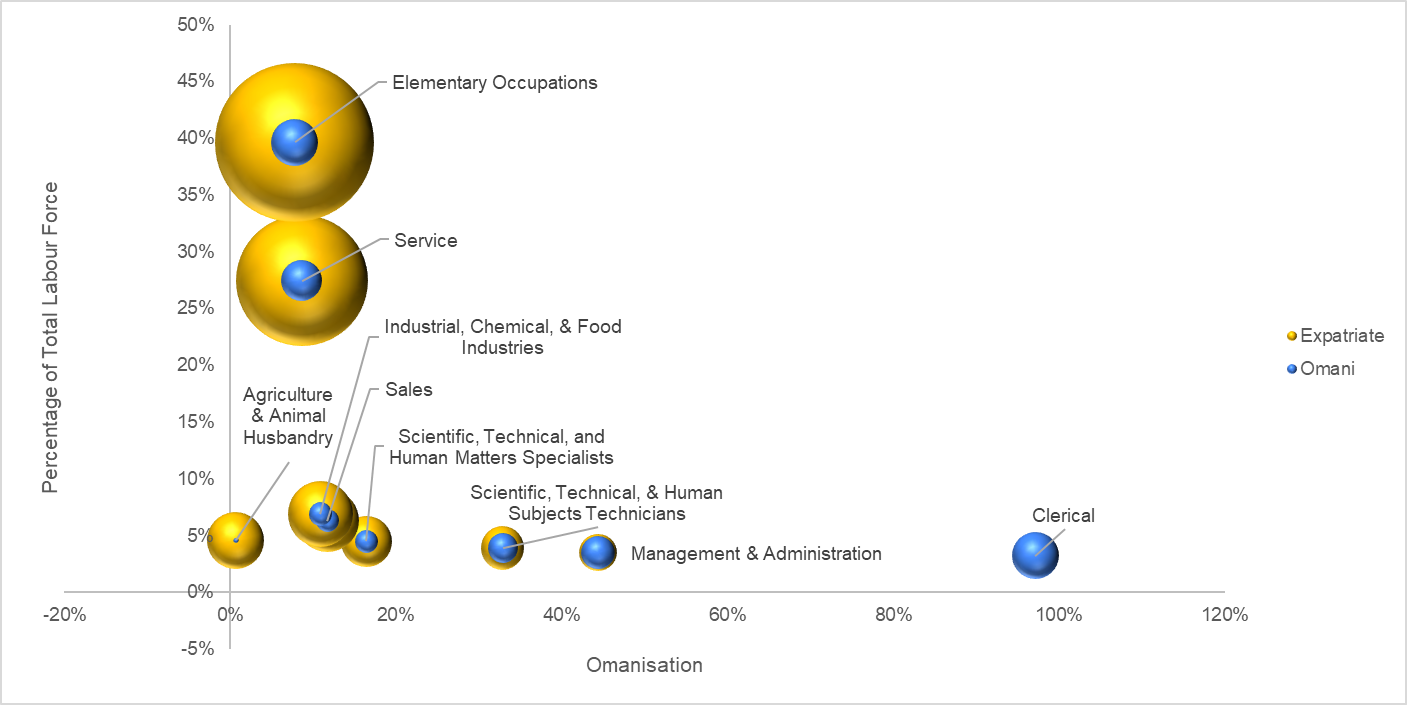

The chapter introduces the book, its main claims, and arguments. It is concerned with setting the agenda for how to take labour seriously in Gulf development discourses and the value of centring labour from the margins. The book argues that Oman’s labour market is global and that Omani labour needs to be understood globally and relationally within and beyond the segmentations that divide the labour market. The chapter situates youth and their economic dreams and experiences at the heart of the story of development, discusses how to understand labour within the rentier state, and lays out the framework and empirical analysis to follow.

Chapter 2: Making Global Labour Markets and National Dreams

This chapter is concerned with recentring labour in regional development accounts and framing the claim of the book that the labour markets of Oman and the region are global. Most development accounts articulate Oman’s labour market as an object of development, a self-contained unit to be regulated and deregulated toward developmental ends. Development policy and academic discourse, in short, treat the labour market as a bounded, local space with enclosed, segmented social relations. In contrast to this development planning imaginary, this chapter argues that the labour market needs to be interpreted in global context and with a view of how regulation and relations transpire within, between, and across segmentations. The labour market is a place in which you can clearly see the outcomes of global market pressures and the competing poles for labour’s management and (de)regulation. These come from within but also outside national and regional boundaries. In combination, by looking from the bottom up, the labour market offers a space where we encounter humans in the economy and can more clearly visualise the human impact of economic transformations and choices.

Chapter 3: Rereading Omani Work History and Labour Market Governance

This chapter offers a critical rereading of Omani work history that foregrounds labour, flipping the perspective from the view of industry and capital to the human experience. Through examining the history of labour governance and resistance in Oman, it argues that the contemporary governance, regulatory, and resistance environment for labour have clear lineages in the past. First, it traverses three key legacies governing work and workers – the colonial modes of circulating, disciplining, and classifying labour, the oil industry’s human resources policies, and the management of labour in national economic planning. Second, the chapter traces discourses about workers and how these discourses and prejudices are persistent technologies of governance that influence practices and assessments of employment and development. Together, this reveals a genealogy of practice and discourse underpinned by racial capitalism that have shaped work life in Oman and the Gulf more widely. Finally, the chapter discusses the various forms of contestation to these practices over time, including connections to worker agitation and mobilisation, strike action, and connections with antiimperialist movements.

Chapter 4: Promising Dubai in Sohar: Radical Transformations and Job Creation from Sohar to Duqm

Offering two case studies – the economic transformations of Sohar and Duqm – this chapter grounds the book’s argument about Oman’s global labour market in material cases of spatial transformation and the integration into global value chains through which both commodities and labour circulate. The chapter argues that millennial citizen expectations take shape in these developments, from the interaction of ostensible outcomes of economic globalisation, neoliberalism, and government responsibilities of governing hydrocarbon windfalls. Citizen reactions emerge from their perceived right to, or exclusion from, these returns. The chapter further substantiates two points through these cases. First, both neoliberal reform and oil wealth explicitly or implicitly make promises to populations about an improved economic life, which, when unrealised, results in disenfranchisement and discontent. Second, capital needs labour and pursues supplies from the global labour market not only because it is cost effective but deliberately because it is both flexible and controllable. It seeks to avert potential labour disruption and secure seamless operations. Together, these findings show the ways Omani labour organises and the power of labour through the threat of its resistance.

Chapter 5: Constructing Belonging and Contesting Economic Space

This chapter explores inclusions and exclusions embedded within the Omani economy as experienced by citizens and foreigners. The chapter shows, first, that contestations around labour market belonging and experiences emerge within the local structures of segmentation and the global nature of Oman’s labour market. Second, in order to understand economic belonging and citizenship in the Gulf, class has to take a central role. The production of difference and competing identities of local regionalism, tribal and community affiliation, religion, interior and coastal cultures, race, heritage, and gender all matter but need to be understood alongside the intervening variable of class. The subjectivity of experiences and perceptions of inclusion and exclusion exposes how the politics and practice of difference in global capitalism produces tensions, value, and forms of power that manifest in labour and class relations. These dynamics also generate resistance and contestation around the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion.

Chapter 6: Pursuing Entrepreneurship for Employment: SMEs for Women and Youth

This chapter examines the promotion of entrepreneurship and business startups in Oman and its rhetorical targeting of youth and women. Although innovation is part of the promotion agenda, entrepreneurship is often focused on encouraging citizens to create their own private sector job. The chapter focuses on the experiences of young people in internalising entrepreneurship promotion discourses and in starting personal businesses. It illustrates two key tensions – first, the tension between rentierism embedded within authoritarian governing structures, on the one hand, and the logic of neoliberal capitalism, on the other; and second, the tensions between rhetoric and realities of youth and female empowerment narratives. Entrepreneurship is expressed and promoted as an empowering activity, and at times is experienced as such, but can also be used to legitimise or reconstitute patriarchal and authoritarian structures to accommodate the market. The space of entrepreneurship promotion is both a key tactic of labour market bandaging, and a distinct illustration of rentier neoliberalism

Conclusion

This chapter offers concluding reflections, taking readers through three intersecting vectors that run through the book. The first establishes how the segmented labour markets of the region are embedded within global structures and processes, which in turn shape domestic and regional structures and the frames through which social relations and regulations unfold. The second vector suggests three historical junctures as especially important in shaping labour trajectories in the region: (1) the partial incorporation of Omani labour and transnational Asian labouring classes into global capitalism through colonial development; (2) the wider integration of Gulf economies and labour markets into global capitalism through the expansion of the oil industry; and (3) the increasing embeddedness of the region in neoliberal capitalism. Finally, the third vector explains the liberalising and nationalising dialectic in labour governance. The heterodox approach of the book offers a direction for future scholarship on the GPE of labour, demonstrating both how empirically-grounded national and regional case studies can highlight and explain global patterns, as well as how the present and future of work in local spaces are entangled within the trajectories of global capitalist development.

This post introducing my book would not be complete without a special note of appreciation to the beautiful work of art featured on the cover by the talented Omani artist, Raya Al-Maskari. I am extremely grateful to her for allowing me to use this work. The painting is entitled bāḥthūn ʿan āml, meaning ‘hope seekers,’ which is a play on words in Arabic to bāḥthūn ʿan ʿaml – job seekers. She first posted it in May 2021, and the painting, to me, exquisitely encapsulates both an awareness and a yearning for hope among a generation of citizens – a hope that is wrapped up in the dream of working.